The Google geofence is the criminal investigative technique that many consider a “magic pill” for their cases. It has the unique ability to identify unknown suspects, but it has limitations. This article discusses what a Google geofence is, how they work, and writing Google geofence search warrants.

It all begins with Sensorvault

Google retains location data for over 200,000,000 devices dating back to 2009 in a database known as Sensorvault. Exactly how Sensorvault works is proprietary so much of what the law enforcement community knows about the system is through trial and error. Google collects location data whenever one of their services is activated and whenever there is an event on the mobile device. Device events include phone calls, text messages, internet access, or email access. Sensorvault also records location data when applications running in the background, even when the user is not interacting with the device. Location data can also be pulled from Google Apps that have appropriately set permissions.

Android vs. iPhone

Every Android based mobile phone has the potential to report location data to Sensorvault. Potentially, Apple iPhones can report data to Sensorvault under the right conditions. I believe that iPhones that have Google apps like Gmail or Youtube running in the foreground have the capability to report location to Google. However, I have not personally observed iOS devices reported in geofence returns. According to Engadget, iPhone overtook the Android ecosystem in June 2022 with a 50% claim of the U.S. market share. This means that there is a 50% chance that the suspect in your crime scene has an Android phone

Note: For a device to report location data back to Sensorvault, all the right conditions must be met: Location services must be on, the phone has a signal, & privacy permissions allow for tracking.

Google Geofence Legal Challenges

Sensorvault data can be searched by Google in the form of a spatial analysis query. The process of specifying a specific geographical area is known as a “geofence” search. The Google geofence search warrant has been in the judicial spotlight most recently in US v. Chatrie. The Chatrie ruling in Virginia is the latest in a confused body of opinions on Fourth Amendment protections of privacy and electronic tracking. Judges struggle with giving police access to the location data of uninvolved law-abiding Americans, however, the Chatrie ruling provides a framework that balances privacy and criminal justice.

When Courts apply the Fourth Amendment to a brand new technology, they use the “reasonable expectations of privacy” test developed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1967 Katz v. United States and the 1978 clarifying case, Smith v. Maryland . The Smith v. Maryland case further defined an appropriate “expectation of privacy” because people voluntarily share data with their phone service providers as a byproduct of their business relationships. It is important to note that in both the Katz and Smith cases, the Fourth Amendment violations were a result of warrantless searches.

Civil-liberties advocates who are unfamiliar with the process and technology believe that a Google geofence is a governmental overreach and a “fishing expedition”. They see geofence warrants as a way for law enforcement to dragnet the personal information of innocent bystanders. In actuality, geofence warrants present an opportunity for sound policing that is consistent with constitutional principles.

Problems Identified in US v. Chatrie

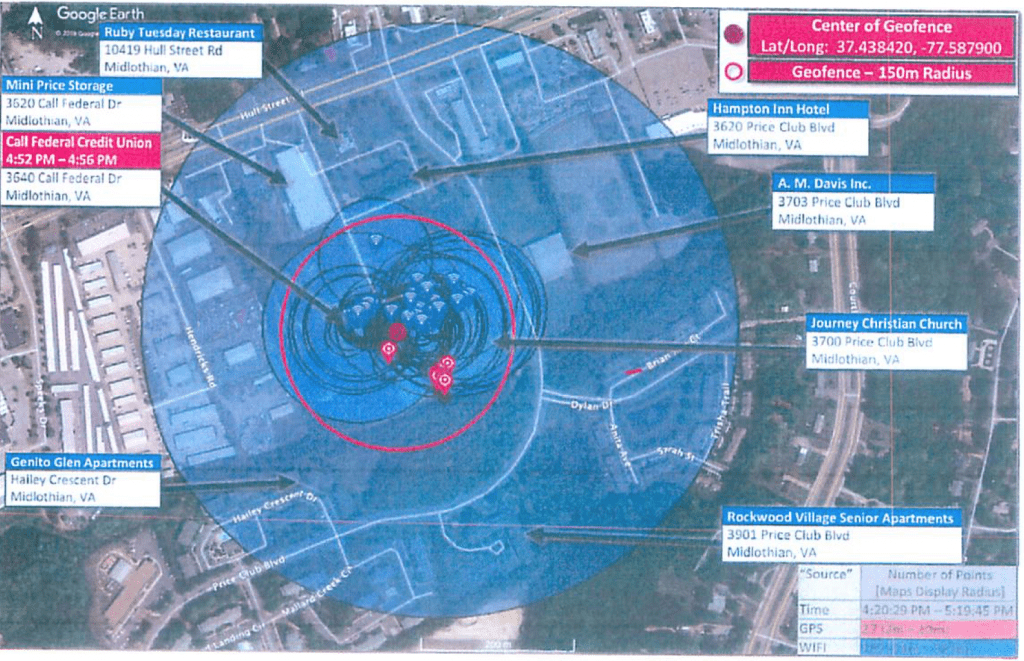

The US v. Chatrie case suffered from two primary problems: an overly broad search area and generic probable cause affidavit. When the law enforcement first began requesting geofence data, they relied on experience from Call Data Records and cell site location. Law enforcement in the Chatrie case defined their search area using a radius from a fixed point. The image below is from the US v. Chatrie case showing the initial search radius in blue. The red marker locations show the devices located within the Initial Search Area as categorized by GPS or Wi-Fi fixes.

Initial Search Area

As you can see from this image, the Initial Search Area was almost a 10th of a mile wide with multiple residences and businesses inside the radius including a restaurant, hotel, part of an apartment complex, a senior living facility and two busy streets. Additionally, the Initial Search spanned the 1 hour period of Monday 5/20/2019 from 1620 hours through 1720 hours. This search area and time frame could easily collect hundreds of people.

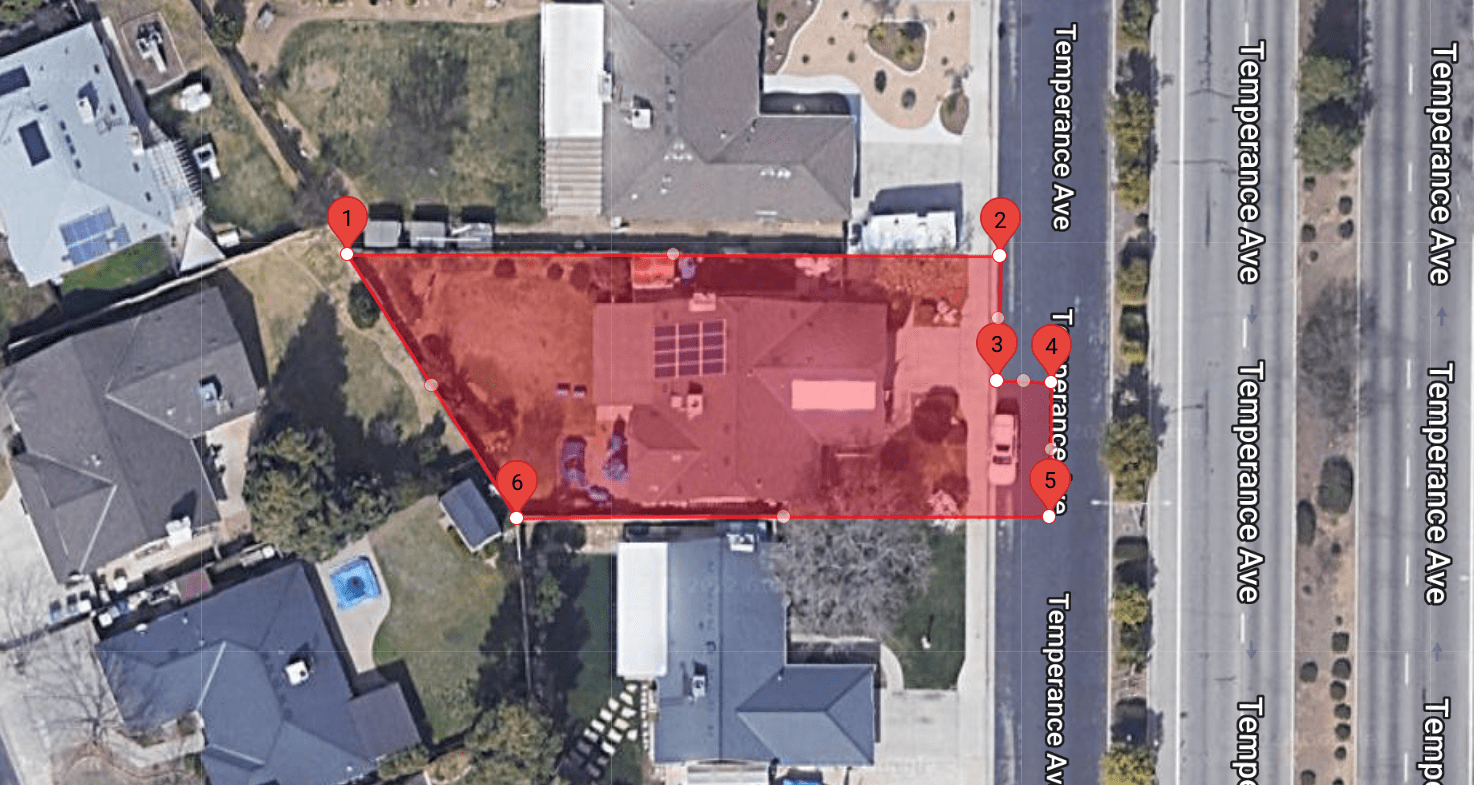

To combat this overcorrection of data, we recommend avoiding radius searches. The WarrantBuilder.com Google Geofence Tool creates Initial Search Areas as polygons so that Investigators can precisely identify the locations to be searched. Shown to the right, the Initial Search Area in red limits the search to only the residence and a small street parking area. It is recommended to narrow the search window to as small of a timeframe as possible. By restricting to a small area and a narrow window, the court can be fairly confident that the only devices located in the search belong to Suspects, Victims or Witnesses.

Probable Cause Problems

Federal District Judge Hannah Lauck criticized law enforcement’s handling of the geofence process in US v. Chatrie by calling out the lack of particularized probable cause at each stage. Judge Lauck cites the generic affidavit and broad scope of the warrant. The probable cause statement in the original search warrant is less than one page. The affidavit didn’t contain any explanation of how geofence would help identify the suspects or how uninvolved parties would be separated.

If the Government is to continue to employ these warrants, it must take care to establish particularized probable cause.

Judge Hannah Lauck – CRIMINAL 3:19cr130 (E.D. Va. Mar. 3, 2022)

When writing Google geofence search warrants with Warrant Builder, the most difficult aspect is laying out particularized probable cause for each part of the process. If two devices are found within a search area, how can you explain why one is more important that the other? The mere fact that both devices are located at the crime scene implies that they are important. To establish particular probable cause, we suggest collecting expanded movement information for these devices. To learn more about particularity, check out our Understanding Search Warrants blog series: Particularity in search warrants.

Multipart Search Warrant Process

Google geofence investigations are a multi-part process. I hesitate to call the process “phases” or “stages” as this implies a linear progression through the parts. The process is comprised of three parts spanning five possible search warrants, however, the facts of the case dictate if all are required. The parts are comprised of:

- Initial Search Area

- Expanded movement information

- Unmasking

In the right circumstances, you may be justified in jumping straight from Initial Search Area to Unmasking. For California law enforcement, it is important to note that any search warrant for geofence records must be CalECPA compliant. Below, each part and required search warrant is discussed.

Initial Search Area

The Google geofence process begins by defining the Initial Search Areas. As discussed above, it is important to keep these areas as small as possible. If the details of your investigation allow for more than one search location, it is best to have at least two. For example, if a two commercial burglaries occurred within hours of each other, creating Initial Search Areas at both crime scenes can help identify the persons who were present at both.

Google prefers to have standard shaped search areas. If the facts of your case require a complex shape like a S or U shape, Google may need to break your search area into smaller individual areas areas. The search warrant return for one Initial Search Area may contain two or more “search areas” within the zip file.

The initial search warrant return comes in the form of a zip file that contains a spreadsheet of all the devices located within the Initial Search Area(s) during the identified timeframe. Each unique device is given a Universally Unique Identifier (UUID) that is a hex value between 76 to 78 characters long. An example UUID is shown below. 010101BD56354DFDABAFEDF11E0CB56744C307180D7E1B4CB323DFEAF8792E6E99ACC5B1A46E

Google assigns these meaningless UUIDs to mask the identity of the device until ordered to unmask it in a separate search warrant. According to Google, once the warrant process is complete these UUIDs are deleted. If a new search warrant for the exact same Initial Search Area is served upon Google, they will produce a different UUID for the same device.

Note: The UUID is an arbitrary identifier that only has meaning to Google for the duration of the geofence process. The device owner has no way of knowing what UUID was assigned to them and there is no way for a person to look up their UUID. Search Warrant Notification is most appropriate once unmasking occurs and an actual customer account is identified.

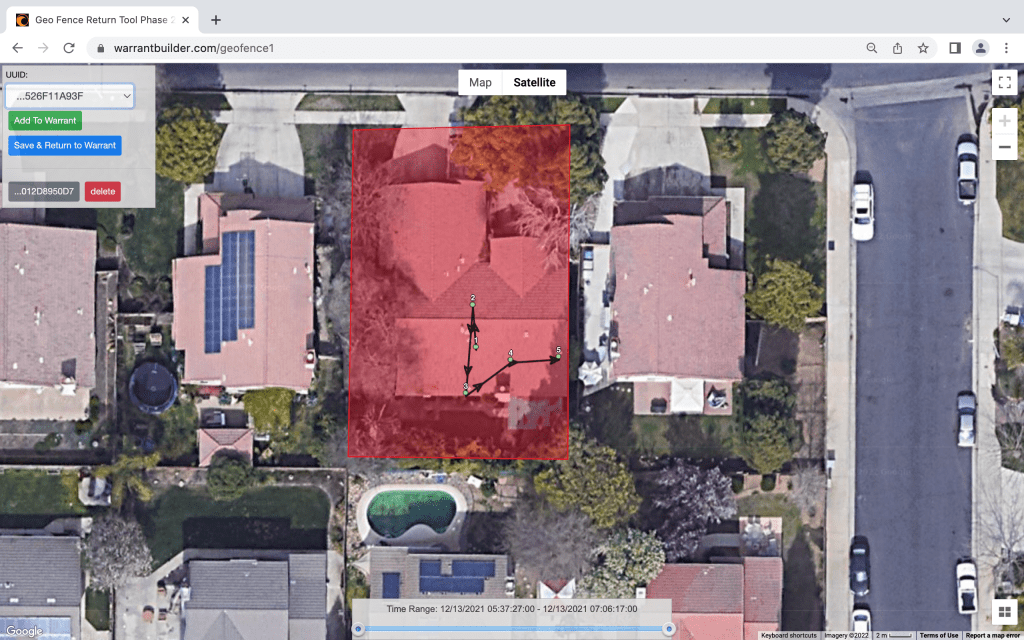

Initial Search Warrant Return: When google responds to the search warrant, the locations must be mapped. WarrantBuilder.com automatically maps returns and organizes them by UUID. The investigator simply selects each from the drop down list to see the device’s location and movement within the initial search area. If that device seems to be relevant to the investigation, it us added to the next part of the search warrant process with just a click.

After the devices have been mapped and added to the search warrant, the Investigator has a decision to make. Would he investigation benefit from knowing where the devices were before the crime, how they moved into the crime scene, and where they went afterward? If so, the next part of the process is a search warrant for Expanded Movement Information. An Investigator can move directly to unmasking if it makes sense; remember, the process is not linear.

Expanded Movement Information

Expanded movement information simply requests location information for specific devices for a period of time before and after the original search. This data may show how the device came into the crime scene, and where they went afterward. When writing Google geofence search warrants with Warrant Builder, the search warrant for specific selected devices is automatically created with one hour before and after the original window.

Unmasking

The final part of the process is the request for unmasking. The unmasking search warrant orders Google to provide basic subscriber information for each UUID. This is where the geofence process technically ends. Records like email content, Google Drive files, Google Photos and more can be collected with a separate search warrant.

Summary

The key to writing Chatrie compliant geofence warrants is a narrow scope and particularized probable cause. The Chatrie warrant failed because of the large search area that could easily collect uninvolved persons and a probable cause statement that was lacking. When writing Google geofence search warrants, make sure your document covers the following:

- Limited Initial Search Areas that exclude uninvolved crime scene surroundings.

- Limit the time frame to as small of a window as reasonable.

- For each search warrant in the process, include particularized probable cause about why the selected devices could be relevant to the investigation.

The easiest way to write a Google geofence warrant is with WarrantBuilder.com. Our automated system guides you through the entire process, maps your returns, and assists in writing the follow up warrants that you need to be successful. Get started writing by signing up for a free trial.